How VR helps to treat PTSD

Find out about Experied Enrichment HERE

It was supposed to be a routine resupply mission: a short drive across the Al Asad Air Base, 90 kilometers north of sweltering Baghdad, to fetch, among other things, a newly-arrived TV to entertain the troops. Jimmy Castellanos, a 20-year-old Marine just five months into his first tour in Iraq, was supposed to be riding on the convoy. But on the afternoon of March 18, 2004 Castellanos, who worked maintaining the weapon systems of the U.S. Army’s Cobra attack helicopters, was told that he was needed for guard duty. His friend and bunkmate took his place.

Around 10 p.m. that night, chased by dust, as if tracing the weakening horizon line between desert and sky, Castellanos watched as the trucks carrying his platoon wended their way home. They were about a kilometer off, but cleanly visible in the desert. When the mortar explosion came, Castellanos wasn’t quite sure what had been hit. A few hours later, news arrived during a casualty briefing: Castellanos’s bunkmate was paralyzed, two other members of the squad had been severely injured, and Cpl. Brownfield, who had sat in Castellanos’s seat, was killed instantly.

The following day the truck was towed back to base, riddled with bullet holes. In the back, the TV, still sleeping in its cardboard box, was now doubly dark brown having soaked up the swill of blood.

When Castellanos returned to America three years later, the effects of the incident began to surface. At night he would check the locks on the windows and doors of his home. He’d go to bed. Then he’d get up to check them again. When he finally fell asleep, he dreamed only of Iraq. When he visited a public bathroom, he would systematically open every stall and look behind every door. Once, someone asked Castellanos about the platoon mate who died that day. Castellanos broke down. “I could not discuss what happened for more than a few seconds without having to leave the room,” he says.

PTSD is not to be taken lightly. And at Experied we are passionate about helping people. To find out more about how VR helps to treat PTSD go to Experied Enrichment HERE

Castellanos, the son of undocumented immigrants who fled El Salvador in 1980 on the eve of civil war, was told endless stories of America’s greatness when he was young. As a teenager, he wanted to give back to the land that gifted his family such opportunity. He joined the military, and after his service, enrolled at Weill Cornell Medical College, in New York, to study a combined MD and PhD in immunology. His tutor, Dr. Olaf Andersen, heard that his student had served in Iraq. When he asked about his experience, Castellanos again broke down in a squall of unsettled grief and anxiety.

Related: Virtual Reality Is Bringing These Lost Worlds Back to Life

For three months, Andersen tried to persuade his student to speak to a psychiatrist. Castellanos resisted. In the military, psychiatrists are considered an enemy. Marines call these doctors “wizards,” not because they had the power to make you better, but because they can make you disappear. “Just requesting to see a chaplain ruined a Marine’s career,” Castellanos says. A single visit to a shrink was enough to ensure you’d lose the respect of your subordinates and any hope of being promoted.

Finally, Castellanos relented. In his first session the psychiatrist wasted no time. “Tell me about your roommate being killed in Iraq,” he asked. Catellanos spent the next ninety minutes in a teary state of bewilderment. “It’s pretty clear to me,” Castellanos recalls the psychiatrist saying, “that you have post traumatic stress disorder. You don’t need medication. You need therapy.”

LIVING WITH PTSD

One in three people who experience an extremely traumatic event — anything from a car accident to a natural disaster to a violent mugging — will suffer from PTSD. The symptoms are often persistent and life wrecking: nightmares, insomnia, and feelings of isolation, irritability, and guilt.

PTSD is not to be taken lightly. And at Experied we are passionate about helping people. To find out more about how VR helps to treat PTSD go to Experied Enrichment HERE

“Think about the worst thing that ever happened to you and remember how you felt immediately afterwards,” says Albert “Skip” Rizzo, a research professor at the USC Davis School of Gerontology who has worked with veterans suffering from the condition since the mid-1980s. “Now imagine that six months later, you still feel that exact same thing with the exact same intensity. That’s PTSD.”

The disorder can lie dormant for years, especially if sufferers are otherwise occupied. According to Rizzo, in 2013 approximately 69,000 brand new cases of PTSD were diagnosed in veterans from Afghanistan and Iraq. That same year, 62,000 Vietnam veterans, who more than thirty years earlier had left that chaotic front, were newly diagnosed with the condition. “As people get older and they retire, they’re not as busy,” Rizzo says. “They get more emotionally vulnerable. That can bring it out.”

Treatment for PTSD has varied over the years, from medication to psychotherapy to simple exercise. Most now agree that exposure therapy, a treatment pioneered in the 1950s that seeks to relive a sufferer’s trauma in a controlled, often imaginary environment, is usually the most effective prescription (though many doctors disagree). The idea is to take a patient back to the memory of their trauma over and over again until their triggers no longer produce anxiety. Psychiatrists call this process habituation. Through repetition, the memory is slowly robbed of its power.

Find out about Experied Enrichment HERE

ENTERING A VIRTUAL WAR ZONE

In 1997, researchers from Georgia Tech linked exposure therapy with the emerging technology of virtual reality. Ten volunteers, veterans suffering from PTSD who had not responded to multiple treatments, signed up for the pioneering clinical trial. It was dubbed Virtual Vietnam.

Each pulled on a VR headset — an off-the-shelf eMagin — and was transported to a jungle clearing, or the passenger seat of a Huey helicopter. A therapist then manipulated the sights and sounds in crude ways, while each patient told of their trauma. After a month’s treatment, all ten patients showed significant improvement.

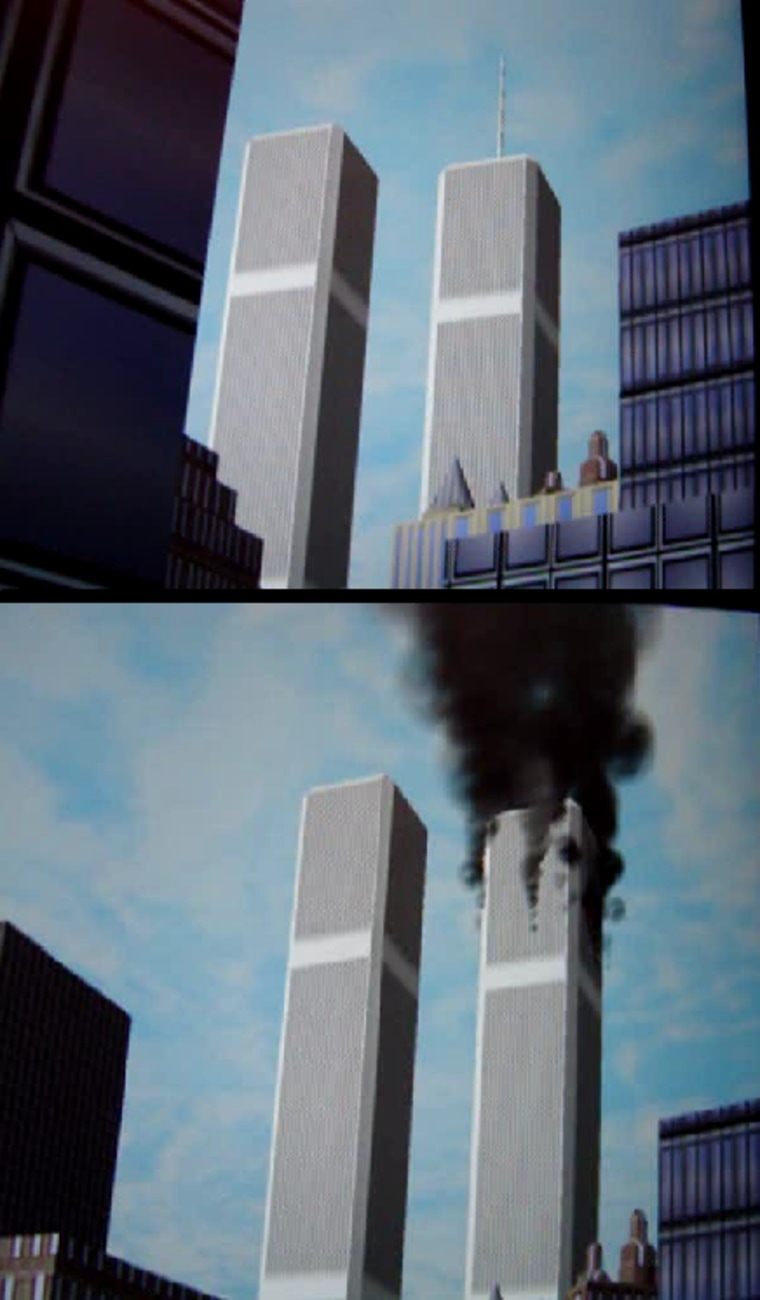

Such was the success of the program that, following the September 11 terrorist attacks on New York’s World Trade Center, one of Rizzo’s collaborators, JoAnn DiFede, began using VR to treat burns victims suffering with PTSD. “People saw the buildings, saw the plane fly into the buildings, heard the sounds and watched the explosion,” she explains. “We did not know if it would work. It did. Better than I ever expected.”

When Castellanos enrolled at Cornell, DiFede, now director of the Program for Anxiety and Traumatic Stress Studies at the university, had expanded her research to look at how the tuberculosis drug D-Cycloserine might be combined with VR to accelerate the treatment’s effectiveness. Working on glutamate receptors in the brain, the drug was shown to enhance learning in rats and mice. DiFede’s idea was that, if patients were given the drug right before the treatment, it would increase the effectiveness of the VR in helping the patient to “relearn.”

“We had a 70 percent remission rate within six months,” she says. Perhaps encouraged by the chance to take place in science-advancing research, Castellanos signed up for DiFede’s trials.

READ MORE HERE

https://www.nbcnews.com/mach/innovation/how-virtual-reality-helping-heal-soldiers-ptsd-n733816